Historical Background to the Ethnic Conflict

The island of Sri Lanka (known as Ceylon until the promulgation of the new Republican Constitution in 1972) is the historical homeland of two ancient civilizations, of two distinct ethno-national formations with different languages, traditions, cultures, territories and histories. The history of the Tamils in the island dates back to pre-historical times. When the ancestors of the Sinhala people arrived in the island with their legendary Prince Vijaya from the ‘city of Sinhapura in Bengal’ in the 6th century BC they encountered ancient Dravidian (Tamil) settlements. Even the Sinhala historical chronicles – Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa – document the existence of Dravidian kingdoms of Nagas and Yakkas before the advent of Sinhala settlers in the island. In an attempt to distort the authentic history of the original settlers, the Buddhist monks, who wrote the historical chronicles, depict the ancient Tamils as ‘nonhumans’ as ‘demons possessing super-human powers’. Though the question of original settlement is obscured by legends and mythologies, modern scholars hold the view that the Tamils were indisputably the earliest settlers. Because of the geographical proximity of southern India to the island, it is highly probable that the Dravidian Tamils were the original inhabitants before the sea landing of Prince Vijaya and his crew from northern India.

The Buddhist historical chronicles record the turbulent historical past of the island from 6th century BC, the history of great wars between Tamil and Sinhala kings, of invasions from southern Indian Tamil empires, of violent struggles for supremacy between Tamil and Sinhala kingdoms. The island was ruled by Sinhalese kings and by Tamil kings at times and the intermittent wars compelled the Sinhala kings to move their capital southwards. From the 13th century onwards, until the advent of foreign colonialism, the Tamils lived as a stable national formation in their own kingdom, ruled by their own kings, within a specified territory of their traditional homelands embracing the northern and eastern provinces.

Marco Polo once described Sri Lanka as the island paradise of the earth. The British colonialists called it ‘the pearl of the Indian ocean’. Separated from the southern coast of India by only a twenty-two mile stretch of water, the island has a territorial area of 25,332 square miles. For centuries before colonial penetration, the island had a traditional self-sustaining economy with a reputation of being the granary of the East. The mode of economic production in the pre-colonial epoch was feudal in character. Structured within the feudal mode, the economic organisation of the Tamil nation had a unique set of relations of production characterised by caste stratification with its hierarchy of functions. The extensive hydraulic agrarian system with its network of tanks and canals for which the mediaeval Ceylon was famous, had fallen out of use and was decaying and disappearing under the thick jungles in the north as well as in the north central provinces. The Sinhalese feudal aristocracy, by this time, had moved to the central highlands and established Kandy as the capital.

When the Portuguese first landed on the island in the beginning of the 16th century, they found two ancient kingdoms, the Tamils in the north-eastern region and the Sinhalese in the south, two distinct communities of people with different cultures constituting themselves as separate nations ruled by their own kings with sovereign state structures. The Portuguese entered into treaties and then fought battles and finally in the battle of 1619 they conquered the Tamil kingdom and hanged the Tamil king Sankili Kumaran. Yet the Portuguese and the Dutch, who came after them, governed the Tamil nation as a separate kingdom, recognising the integrity of the Tamil homeland and the ethnic identity of the Tamil people. In 1796 the British colonial empire took control of the island from the Dutch and in 1833 imposed a unified state structure amalgamating the two national formations irrespective of the ethnic differences. Thus foreign colonialism laid the foundation for the present national conflict. Though the British, for administrative purposes, created a unitary state, they recognised that the island had been the homeland of two separate nations. In 1799 Sir Hugh Cleghorn, the first Colonial Secretary observed in the well known ‘Cleghorn Minute’, ‘two different nations, from very ancient period have divided between them the possessions of the island: the Sinhalese inhabiting the interior in its southern and western parts from the river Wallouve to that of Chillow, and the Malabars (the Tamils) who possess the northern and eastern districts. These two nations, differ entirely in their religion, language and manners.’

Though the Sinhalese and the Tamils have an ancient past with deep historical roots buried beyond the Christian era and possess elements of distinct nations, the island of Sri Lanka, in the course of history, developed a heterogeneous culture. There are other ethnic groups living in the island, of which the Muslims and the plantation Tamils constitute themselves as significant communities of people with distinct cultural identities.

The Sri Lankan Muslims, whose origins can be traced back to the 10th century, arrived in the island as traders from Arabia. The Muslims adopted the Tamil language as their mother tongue and settled down predominately in the eastern region and in the southern districts. Though they embraced Tamil language and shared a common economic existence with the Tamils as a peasant community in the east, it is their religion, Islam, which provides them with the consciousness of collective cultural identity as a distinct ethnic group.

British Colonialism and the Tamils

The effects of Portuguese and Dutch colonial rule on the island’s pre-capitalist economic formation are minimal when compared to the profound effects of British colonial domination. The most significant event of British colonial rule was the imposition of an exploitative plantation economy.

It was in 1815, with the conquest of the Kandyian kingdom by the British, the painful history of the Tamil plantation workers begins. It was during that time the British colonialists decided to introduce the plantation economy in the island. Coffee plantations were set up in the early 1820s, a crop which flourished in high altitudes. Speculators and entrepreneurs from England rushed to the newly conquered mountain areas and expropriated vast tracts of land, by deceit, from the Kandyian peasantry. The Kandyian peasants refused to abandon their traditional subsistence holdings to become wage earners on these new capitalist estates. The pressure exerted by the colonial state to draw the labour power from the indigenous Sinhalese peasantry did not work. The British colonial masters were thus compelled to draw on their limitless reserves of labour from India. A massive army of cheap labourers were conscripted from southern India who, partly by their own poverty and partly by coercion, moved into this Promised Land to be condemned to an appalling form of slave labour. A notorious system of labour contract was established which allowed hundreds of thousands of Tamil labourers to migrate to the plantation estates. Between the 1840s and 1850s a million people were imported. The original workers were recruited from Tamil Nadu districts of Tinneveli, Madurai and Tanjore and were from the poor, oppressed castes. This army of recruited workers were forced to walk hundreds of miles from their villages to Rameswaram and again from Mannar through impenetrable jungles to the central hill-lands of Ceylon. Thousands of this immiserated mass perished on their longhazardous journey, a journey chartered with disease, death and despair. Those who survived the journey were weak and exhausted and thousands of them died in the nightmarish, unhealthy conditions of the early plantations.

The coffee plantation economy collapsed in the 1870s when a leaf disease ravaged the plantations. But the economic system survived intact with the introduction of a successor crop – tea. Tea was introduced in the 1880s on a wide scale. The tea plantation economy expanded with British entrepreneurial investment, export markets and consolidated companies transforming the structure of production and effectively changing the economic foundation of the old feudal society creating a basis for the development of the capitalist economic system. Though the plantation economy effectively changed the process of production, the Tamil labourers – men, women and children – were permanently condemned to slave under the white masters and the indigenous capitalists. The British planters who brought the Indian Tamil labourers into Sri Lanka deliberately segregated them inside the plantations in what is known as the ‘line rooms’. Such a notorious policy of segregation condemned the Tamils permanently to these miserable ghettos, isolated them from the rest of the population and prevented them from buying their own land, building their own houses and leading a free social existence. British colonial rule built up the Tamil plantation community within the heartland of the Kandyian Sinhalese and manipulated the Tamil-Sinhala antagonism to divide and rule. Reduced to conditions of slavery by colonialism, the Tamil plantation workers toiled in utter misery. Their sweat and blood sustained the worst form of exploitative economy that fed the English masters with the surplus value and enriched the Sinhala land owning classes.

The impact of British colonial domination on the indigenous Tamil people of the northern and eastern provinces had far reaching effects. On the political level, British colonial rule imposed a unified administration with centralised institutions, establishing a singular state structure. This forceful annexation and amalgamation of two separate kingdoms, of two nations of people, disregarding their past historical existence, their socio-cultural distinctions and their ethnic differences are the root causes of the Tamil-Sinhala racial antagonism.

The Tamil social formation was constituted by a unique socioeconomic organisation, in which feudal elements and caste systems were tightly interwoven to form the foundation of this complex society. The notorious system of caste stratification bestows, by right of birth, privilege and status to the high caste Tamils. The most exploited and oppressed people are from the so-called depressed castes who eke out a meagre existence under this system of slavery. Privileged by caste and provided with better educational facilities by foreign missionaries, a section of the high caste Tamils adopted the English educational system. A new class of English educated professional and white-collar workers emerged and became a part of the bureaucratic structure of the civil service. The English colonial masters encouraged the Tamils and provided them with an adequate share in the state administration under a notorious strategy of divide and rule, that later sparked the fires of Sinhala chauvinism.

The Tamil dominance in the state administrative structure, as well as in the plantation economic sector, the privileges enjoyed by the English educated elites and the spread of Christianity are factors that propelled the emergence of Sinhala nationalism. In the early stages, nationalist tendencies took the form of Buddhist revival, which gradually assumed a powerful political dominance. Under the slogan of Buddhist religious renaissance, a national chauvinistic ideology emerged with strong sediments of Tamil antagonism. The Buddhist religious leadership attacked both the Tamils and European colonialists and spoke of the greatness of the Sinhalese Aryan race.

Anagarika Dharmapala, a Buddhist thinker, wrote in his popular work, ‘History of an Ancient Civilization’, ‘ethnologically, the Sinhalese are a unique race, inasmuch as they can boast that they have no slave blood in them, and were never conquered by either the pagan Tamils or European vandals who for three centuries devastated the land, destroyed ancient temples and nearly annihilated the historic race. This bright, beautiful island was made into a paradise by the Aryan Sinhalese before its destruction was brought about the barbaric vandals….’

The Sinhala national chauvinism that emerged from the Buddhist religious resurgence viewed the Tamil dominance in the state apparatus and in the plantation economy as a threat to ‘national development’. Such anti-Tamil antagonism articulated on the ideological level began to take concrete forms of social, political and economic oppression soon after the island’s independence in 1948 when the state power was transferred to the Sinhala ruling elites.

State Oppression Against Tamils

Soon after the transfer of political power to the Sinhalese majority, national chauvinism reigned supreme and fuelled a vicious and violent form of state oppression against the Tamil people. State oppression has a continuous history of more than half a century since independence and has been practised by successive Sri Lanka governments. The oppression has a genocidal intent involving a well-calculated plan aiming at the gradual and systematic destruction of the essential foundations of the Tamil nation. The state oppression therefore assumed the multi-dimensional thrust, attacking simultaneously on different levels of the conditions of existence of the Tamil people. It imperilled their linguistic rights, the right to education and employment; it deprived them of their right to ownership of their traditional lands; it endangered their religious and cultural life and as a consequence posed a serious threat to their very right to existence. The state oppression, in essence, struck the very foundations of the ethnic cohesion and identity of the Tamil people. As an integral part of this genocidal programme, the state organised periodical communal holocausts, which plagued the island, resulting in mass extermination of Tamils and the massive destruction of their property.

Soon after the independence of the island the Sri Lanka Parliament became the very instrument of majoritarian tyranny where racism reigned supreme and repressive laws were enacted against the minority communities. The first victims of the Sinhala racist onslaught were the Tamil plantation workers. A million of this working people, who toiled for the prosperity of the island for more than a century, were disenfranchised by the most infamous citizenship legislation in Sri Lankan political history, which robbed these people of their basic human rights and reduced them to an appalling condition of statelessness. Having been deprived of the right of political participation, the state Parliament was closed for this huge mass of working people. Before the introduction of these laws, seven members of Parliament represented the plantation Tamils. In the general election of 1952, as a direct consequence of these citizenship laws not a single representative could be returned.

The Citizenship Act of 1948 and the Indian Pakistani Citizenship Act of 1949 laid down stringent conditions for the acquisition of citizenship by descent as well as by virtue of residence for a stipulated period. These Acts were implemented in such a manner that only about 130,000 out of more than a million people were able to acquire citizenship. The cumulative effects of these notorious legislations were so disastrous that made the conditions of life of these working people miserable and tragic. Having been reduced to a condition of statelessness, nearly a million Tamils were denied the right to participate in local and national elections; were denied employment opportunities in the public and private sectors; were denied the right to purchase lands; were denied the right to enter business of any sort. Such a condition of statelessness condemned this entire population of workers, the classical working class of the island, into a dehumanised people devoid of any rights and dumped them perpetually in their plantation ghettos to suffer degradation and despair.

The most vicious form of oppression calculated to destroy the ethnic identity of the Tamils was the aggressive state aided colonisation, which began soon after Independence, and has now swallowed nearly three thousand square miles of Tamil territory. This planned occupation of Tamil lands by hundreds of thousands of Sinhala people, aided and abetted by the state, in the areas where a huge population of landless Tamil peasantry had been striving for a tiny plot to toil, was aimed to disrupt the demographic pattern and to reduce the Tamils to a minority in their own historical lands. The worst affected areas are in the eastern province. The gigantic Gal Oya and Madura Oya development schemes have robbed huge bulks of land from the Muslim people of Batticaloa district. Sinhala colonisation schemes in Allai and Kantalai and the Yan Oya project have engulfed the Trincomalee area. This consistent policy of forceful annexation of Tamil traditional land exposes the vicious nature of the racist policies of the Sinhala ruling elites.

The state oppression soon penetrated into the sphere of language, education and employment. The ‘Sinhala Only’ movement spearheaded by Mr SWRD Bandaranayake brought him to political power in 1956. His first Act in Parliament put an end to the official and equal status enjoyed by the Tamil language and made Sinhala the only official language of the country. The ‘Sinhala Only Act’ demanded proficiency in Sinhala in the civil service. Tamil public servants, deprived of the rights of increments and promotions, were forced to learn the Sinhala language or leave employment. Employment opportunities in the public service were practically closed to Tamils.

Education was the sphere where state oppression struck most deeply to deprive a vast population of Tamil youth of access to higher education and employment. A notorious discriminatory selective device called ‘standardisation’ was introduced in 1970, which demanded higher marks from the Tamil students for university admissions whereas the Sinhalese students were admitted with lower grades. This discriminatory device dramatically reduced the number of admissions of Tamil students to universities and seriously undermined their prospects of higher studies.

State oppression also showed its intensity in the economic strangulation of the Tamil nation. Apart from a few state-owned factories built soon after independence, Tamil areas were totally isolated from all national development projects for nearly fifty years. While the Sinhala nation flourished with massive development projects, the Tamil nation was alienated as an unwanted colony and suffered serious economic deprivation.

The anti-Tamil riots that periodically erupted in the island should not be viewed as spontaneous outbursts of inter-communal violence between the two communities. All major racial conflagrations that erupted violently against the Tamil people were inspired and masterminded by the Sinhala regimes as a part of a genocidal programme. Violent anti-Tamil riots exploded in the island in 1956, 1958, 1961, 1974, 1977, 1979, 1981 and in July 1983. In these racial holocausts thousands of Tamils, including women and children were massacred in the most gruesome manner, billions of rupees worth of Tamil property was destroyed and hundreds of thousands made refugees. The state’s armed forces colluded with Sinhalese hooligans and vandals in their violent rampage of arson, rape and mass murder.

The cumulative effect of this multi-dimensional oppression had far reaching consequences. It threatened the very survival of the Tamil people. It aggravated the ethnic conflict and made reconciliation and co-existence between the two nations extremely difficult. It stiffened the Tamil militancy and created conditions for the emergence of the Tamil armed resistance movement. It paved the way for the invocation of the Tamil right to self-determination and secession.

Tamil National Movement and the Federal Party

Tamil nationalism as an ideology and as a concrete political movement thus arose as a historical consequence of Sinhala chauvinistic state oppression. As a collective sentiment of an oppressed people awakening their national self-consciousness, Tamil nationalism contained within itself progressive and revolutionary elements. It was progressive since it expressed the profound political aspirations of the oppressed Tamil masses for freedom, dignity and justice. It had a revolutionary potential since it was able to mobilise all sections of the Tamil people and poised them for a political struggle for national freedom.

In the early stages of the evolutionary political history of the Tamils, Tamil national sentiments found organisational expression in the Federal Party. (The Tamil designation of the Federal Party was Ilankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi. The late Mr SJV Chelvanayakam founded it in December 1949). At the general election of 1956, the Federal Party swept to victory in Tamil electorates and emerged as a powerful political force to spearhead the Tamil national movement. As a national movement championing the cause of the Tamil nation, the party did contain progressive and democratic contents and was able to organise and mobilise various strata of classes and castes into a huge mass movement.

The failure of the Left movement to establish a strong political base among the Tamil people was due to its lack of political vision in comprehending and situating the concrete conditions of national oppression. Positing the class struggle over and against the national struggle of an oppressed nation they conceived the national patriotic upsurgence of the Tamil masses as the manifestation of a reactionary form of ethno-nationalism ignoring the progressive and revolutionary potential of the struggle. Their lack of theoretical perspective in this crucial domain allowed them to speak of ‘proletarian internationalism’ without realising the political truth that national oppression is the enemy of class struggle and that working class solidarity is practically unattainable when national oppression presents itself as the major contradiction between the two nations. The success of the Federal Party in securing popular mass support lies in the fact that they apprehended the onslaught of Sinhala state oppression against the Tamil nation. The thrust of the multi-dimensional oppression, the leadership rightly perceived, would jeopardise the identity and cohesiveness of the Tamil national formation. Warning of this impending danger, they campaigned and organised all sections of the Tamil masses, invoking the spirit of nationalism. The Federal Party thus emerged as a powerful national movement unifying the formless conglomeration of classes and castes into popular mass movement poised for sustained democratic struggles.

The adamant determination of the government of Mr Bandaranayake to implement the Sinhala Only Act became a crucial political challenge to the Federal Party, which decided to launch a Satyagraha campaign (passive, peaceful, sit-in protests of Gandhian non-violent method) as a form of popular resistance. It was on the morning of 5 June 1956, when Parliament assembled to debate the Sinhala Only Act the Federal Party Parliamentarians, party members and sympathisers in their hundreds performed satyagraha on the Galle Face green just opposite the Parliament building in Colombo. Within hours the satyagrahis were mobbed by thousands of Sinhala hooligans who stoned and assaulted the peaceful picketers. When the situation became uncontrollable and dangerous, the Federal Party leaders called off the protest. The rioters, who harassed and persecuted the satyagrahis, went on a bloodthirsty rampage in the capital city assaulting the Tamils and looting their property. The riot soon spread to several parts of the island with violent incidents of murder, looting, arson and rape. In Amparai, more than one hundred Tamils were massacred.

Irrespective of the spreading communal violence and the Tamil protest campaign, the Sinhala Only Act was passed and the Tamil language lost its official status.

Following the implementation of the Sinhala Only Act, the Federal Party organised mass agitation campaigns demanding a federal form of autonomy for the Tamil nation. In the elections of 1956, the Federal Party won an overwhelming victory, obtaining a clear mandate from the Tamil people for a federal form of self-government. The Federal Party also made a decision to intensify the Satyagraha campaign to achieve its demands. The demand for political autonomy for the Tamil nation, along with the rising wave of Tamil nationalism, alarmed the Sinhala ruling elite. Mr Bandaranayake, in a desperate attempt to arrest the growing conflict, agreed to give concessions to the Tamils. A pact was signed between him and the Federal Party leader, Mr SJV Chelvanayagam, that provided some elements of political autonomy under regional councils, with a promise to stop Sinhala colonisation of Tamil areas. The pact sparked suspicion and resentment among the Sinhala racist elements. The man who exploited this explosive situation was a JR Jayawardane, who later became the powerful President of Sri Lanka. Jayawardane, with the support of Buddhist monks, organised a massive protest march to Kandy demanding the abrogation of the pact. This Sinhala chauvinistic upsurgence even inspired some ministers of Mr Bandaranayake’s Cabinet to organise a protest of their own against the pact. Led by these ministers, a long procession of bhikkus (monks) and their racist sympathisers marched to the Prime Minister’s residence carrying a copy of the pact in a coffin. The communal drama finally ended with the ceremonial burning of the coffin in front of the Prime Minister’s official residence at Rosemead Place in Colombo where Mr Bandaranayake made a solemn pledge to abrogate the pact.

This great betrayal by the Sinhala political leadership blew up all hopes of racial harmony and the relations between the two nations became hostile. The ethnic friction gradually became intense and exploded into violent racial riots in 1958. This communal fury that ravaged throughout the island stained the pages of Sri Lanka’s history with blood. The horror and savagery perpetrated against innocent Tamils are indescribable. Several hundreds were butchered, pregnant women were raped and murdered; children were hacked to death. In Panandura a Hindu priest was burnt alive. Several mutilated bodies were found in a well at Maha Oya. In Kalutara a Tamil family, while attempting to hide in a well, had petrol poured over them and when they begged for mercy they were set on fire. As the cries of agony arose when they were being roasted alive in a huge fireball, the racist spectators laughed and danced, enthralled by sadistic ecstasy. Hundreds of thousands lost their homes and several billions worth of Tamil property were either looted or burnt to ashes. While the flames of racial horror were consuming the whole island, Mr Bandaranayake watched this tragic holocaust with amusement and refused to declare a State of Emergency until the Tamils, as he was reported to have said, ‘get a taste of it’. After twenty-four hours of calculated delay, a State of Emergency was declared. When the situation was brought under control, ten thousand Tamils were refugees, most of them civil servants, professionals and businessmen from Colombo who had to be shipped to the northern and eastern provinces for safety.

The Satyagraha Campaign

The 1958 racial holocaust cut a deep wedge in the relations between the Tamil and Sinhala nations. Tamil national sentiments ran high and erupted into massive agitation campaigns on the Tamil political arena. It was in the early part of 1961 that the Federal Party decided to launch direct action in the form of satyagraha in front of government offices in the northern and eastern provinces. The objective was to disrupt and disorganise the government’s administrative structure in the Tamil homeland thereby exerting pressure on the government to accept the Tamil demand for federal autonomy.

The Satyagraha campaign of 1961 was a monumental event in the history of the Tamil national struggle. The campaign unfolded into a huge upsurgence of the popular Tamil masses to register a national protest against the oppressive policies of the Sinhala ruling elites. This Civil Disobedience Campaign, which was inaugurated on the 20 February 1961 and lasted nearly three months, brought hundreds of thousands of Tamil people onto the streets to express their defiance and dissent to the oppressive state. Within a couple of weeks the whole government administrative machinery in the north and east was paralysed and the Tamil nation was practically cut off from the writ of the central government. This unprecedented historical event displayed the fast growing national solidarity of the Tamils and demonstrated their collective determination to fight for their political rights.

The campaign started as massive picketing in front of the government’s main administrative office in Jaffna and soon spread to Vavuniya, Mullaitivu, Mannar, Trincomalee and Batticaloa and other towns. All sections of the Tamil speaking people, irrespective of religious and caste differences, enthusiastically participated in this peaceful popular protest. Thousands of plantation workers from the hill country areas converged in the north and east to express their militant solidarity. This massive national uprising encouraged the Federal Party leadership to open a postal service on the 14 April 1961 and Tamil national stamps were issued in thousands as an act of defiance against the state authority.

Alarmed by the rising tide of Tamil nationalism and the extraordinary success of the Civil Disobedience Campaign, the state oppressive machinery reacted swiftly, mobilising the military. Large contingents of armed forces were dispatched to Tamil areas with ‘special instructions’ under Emergency powers. In the early hours of the 18 April 1961, troops suddenly swooped down on the satyagrahis in Jaffna and brutally attacked them with rifle butts and batons, fracturing skulls and limbs. This barbarous military violence unleashed against the non-violent agitators resulted in hundreds of them sustaining serious injuries. Under the guise of Emergency and curfew, military terrorism was let loose all over the Tamil homeland, suppressing the agitation with brutal violence. The Tamil leaders were arrested, the Federal Party offices were ransacked and the situation, in the government’s view ‘was brought under control’. Thus the violence of the oppressor silenced the nonviolence of the oppressed; the armed might of Sinhala chauvinism crushed the ‘ahimsa’ of the aggrieved Tamils. This historical event marked the beginning of a political experience that was crucial to the Tamil national struggle, an experience that taught the Tamils that the moral power of non-violence could not challenge the military power of a violent oppressor whose racial hatred transcends all ethical norms of humanness and civilized behaviour. To the oppressor this event encouraged the view that military terrorism is the only answer to the Tamil political struggle and that the non-violent foundation of the Tamil political agitation is weak and impotent against the barrel of the gun.

In 1965 the United National Party (UNP) assumed political power. The Federal party decided to collaborate with this so-called ‘national government’ with the expectation of wrenching some concessions for the Tamils. This collaborationist strategy, the Tamil leadership vainly hoped, would bring a negotiated settlement to the Tamil question. The UNP government, in a shrewd move to placate the Tamil nationalists, appointed a senior Federal Party member to its Cabinet and in the following year promulgated regulations defining certain uses of the Tamil language in the transaction of government business. A secret pact was also made between SVJ Chelvanayagam, the Federal Party leader and the UNP leader and Prime Minister, Dudley Senanayake, making provisions for the establishment of district councils.

Neither the regulations for the use of Tamil language nor the promise of decentralisation of political power to regional bodies were implemented. The communal politics of the Sinhala political leadership never allowed for a mechanism of negotiated settlement. A typical historical pattern was established that when the party in power attempted a negotiated settlement to the Tamil question, the party in opposition invoked anti-Tamil sentiments to undermine the move, thereby scoring political victory over its opponent as champions and guardians of Sinhala ‘patriotism’. Caught up in this political duplicity, the UNP government abrogated the pact when confronted with the pressure of Sinhala opposition. Thus, the collaborationist strategy of the Federal Party suffered the inevitable fate of betrayal and, in humiliation, the party withdrew its support to the government in 1968.

JVP’s Insurrection

Critical events of far-reaching political significance dominate the pages of Sri Lankan political history during the period from 1970 to 1977. This historical conjuncture marked the reign of an infamous regime constituted by left wing politicians who, under the slogan of ‘democratic socialism’, brought havoc and disaster to the entire country. This period was characterised by insurrectionary youth rebellion in the south and heightened political violence in the north, denoting the mounting frustration and anger of the younger generations against the repressive state. It was during this period that ethnic contradiction between the Tamils and the Sinhalese became acute with the introduction of a new republican constitution that gave institutional legitimacy to Sinhala-Buddhist hegemony in the island. This eventful period gave birth to the Tamil Tiger guerrilla movement and the growth of the armed resistance campaign of the Tamils. It was during this period that the Tamil national movement opted to invoke the Tamil’s right to self-determination and resolved to pursue the path of secession and political independence.

An alliance between Srimavo Bandaranayake’s Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and the traditional old Left, the Trotskyite Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) and the Communist Party of Sri Lanka (CPSL), brought to political power in 1970 what is mistakenly called the ‘Popular Front’ government. As soon as the new government assumed power it was confronted with a Sinhala youth insurrection. In an ill conceived and adventurous attempt to wrench power from the state, the newly formed Marxist militant organisation, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP or People’s Liberation Front) rose in rebellion in the south. The rebellion was poorly organised, without a command and control structure, without a coherent policy and strategy. The leadership of the ‘revolution’ was thoroughly disorganised and lacked any understanding or practical experience in armed revolutionary struggle. Rohana Wijeweera, the JVP’s leader was an amateur in the art of armed struggle but ambitious enough to mastermind a major insurrection with the limited textual knowledge gathered from the Russian October Revolution, Mao Zedong’s military writings and Che Guevara’s notes on guerrilla warfare. While ignoring the objective and subjective conditions of a revolutionary situation, the movement mobilised unemployed militant youth and sections of the landless peasantry for a popular rebellion. Beginning on the 5 April 1971, this sudden uprising took the form of widespread armed assaults on local police stations. Within days, ninety-three local police stations were overrun by the JVP’s militant cadres and several administrative districts in the south fell to rebel hands. Though this sudden uprising took the government by surprise, the state machinery took swift counterinsurrectionary measures to contain the situation. State of Emergency and curfews were declared and the government called for urgent military assistance from foreign countries. India, China, Pakistan and Britain rushed in military equipment. India provided a contingent of commandos to protect the capital, Colombo. Armed to the teeth by foreign military assistance and invested with draconian emergency powers, the Sri Lankan armed forces launched a brutal counter-offensive against the young, inexperienced ‘revolutionaries’. It was the most barbaric military suppression in Sri Lankan history. To bring the situation under control more than ten thousand Sinhalese youth were mercilessly slaughtered and another fifteen thousand imprisoned. This violent counter offensive campaign wiped out a whole generation of radical Sinhala youth who sincerely believed that a revolutionary insurrection would redeem them from the misery and despair of unemployed existence. The stream of blood that ran from these butchered innocents stained every inch of the acclaimed holy land of compassionate Buddhism. The shame of history befell on those who masterminded this mass extermination, on those who wiped out thousands of their own children to stabilise their own political power. In this Hitlerian determination to wipe out by brutal force any further rebellion emanating from the oppressed sections, the governing elite enacted Emergency Laws and other repressive legislations and strengthened its grip on state power.

Having violently suppressed the militant Sinhala youth, the new regime turned its oppressive measures towards the Tamils in an attempt to legalise and institutionalise state oppression. The most important measure in this respect was the adoption of a new Republican Constitution, which reaffirmed Sinhala as the sole official language, and conferred a pre-eminent status on Buddhism. The new constitution not only removed the fundamental rights, privileges and safeguards accorded to ‘national minorities’ under section twenty-nine of the previous Soulbury Constitution, but also made Mr Bandaranayake’s racist laws on language and religion as the supreme laws of the land.

Chapter 3, Article 7 of the new constitution stated: ‘the official language of Sri Lanka shall be Sinhala as provided by the Official Language Act, No 33 of 1956’. The primacy of Buddhism was accorded in the following words: ‘the Republic of Sri Lanka shall give to Buddhism the foremost place and accordingly it shall be the duty of the State to protect and foster Buddhism while assuring to all religions the rights granted by Section 18 (1) (d)’.

The Constituent Assembly categorically rejected all amendments and resolutions proposed on behalf of the Tamil speaking people. A comprehensive federal scheme proposed by the Federal Party was tuned down without even discussion. All efforts to secure a place in the new constitution for the use of the Tamil language ended in fiasco. Sinhala national chauvinism reigned supreme in the deliberations of the Assembly, which resulted in most of the Tamil members of Parliament walking out in utter frustration and hopelessness. This infamous constitution, which was passed on the 22 May 1972, brought an end to Tamil participation in the sharing of state power and created a condition of political alienation of a nation of people.

It must be noted that the major political parties that represented the Sinhala nation, the UNP and the SLFP, have consistently and deliberately denied the basic political rights of the Tamils. The Trotskyite LSSP and the Communist Party, who championed the rights of the Tamils in the 50s, succumbed to political opportunism in the early 60s and embraced the politics of Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism. The persistent arrogance and determination of all major Sinhala political parties to deny them their rights drove home to the Tamils the utter futility of striving for ethnic reconciliation. The political forces of the Sinhala nation converged for confrontation rather than co-existence, and compelled the Tamil people to opt to determine their own political status and destiny. This objective condition led to the consolidation of Tamil political forces into a united national movement to struggle for a common cause. The major event in this direction took place at an all-party conference held at Trincomalee on 14 May 1972 in which the Federal Party, the Tamil Congress and the Ceylon Workers Congress united to form the Tamil United Front (TUF). This unprecedented move demonstrated the unitary cohesion and resolve of the Tamil people to fight to preserve their national identity and political liberty.

Political Violence of the Tamil Youth

Though the leadership of the Tamil United Front (TUF) realised the urgency of unity and collective action based on a pragmatic political strategy, differences of opinion among the leaders prevented them from formulating an action plan. The outright rejection of the proposals submitted on behalf of the Tamil nation at the Constituent Assembly was a serious matter of concern. It entailed total denial to the Tamil people of any meaningful access in government. It also meant absolute marginalisation of the Tamils from the Sri Lanka political system. The leaders did realise that the political future of the Tamil nation was in serious danger. Yet they could not work out a practical programme of action to advance the struggle to secure the political rights of our people. The following six point programme adopted at the Trincomalee conference clearly betrays the inadequacy of the political vision of the TUF leadership:

1. A defined place for Tamil language.

2. Sri Lanka should be a secular state.

3. Fundamental rights of ethnic minorities should be embodied in the constitution and made enforceable by law.

4. Citizenship for all who applied for it.

5. Decentralisation of the administration.

6. Caste system to be abolished.

While the Sinhala political parties, with a wider consensus, formulated and promulgated a rigid, entrenched constitution creating a Sinhala-Buddhist autocratic state structure, the Tamil leaders could only work out a few vague demands that fell woefully short of their original goals and failed to address the political aspirations of the Tamil people.

The politically conscious Tamil militant youth became disenchanted with the Tamil leadership for their lack of vision and political inaction. Disillusioned with the political strategy of non-violence, which the Tamil nationalist leadership had been advocating for thirty years and had produced no political fruits, the Tamil youth demanded drastic and radical action for a swift resolution to the Tamil national question. Caught up in a revolutionary situation generated by the contradiction of ethnic oppression and constantly victimised by political brutality, the youth were forced to abandon the Gandhian doctrine of ‘ahimsa’ (non-violence), which they realised was irreconcilable with revolutionary political practice and inapplicable to the concrete conditions in which they were situated. The political violence of the youth, which began to explode on the Tamil political scene in the early seventies and took organised forms of resistance in the later stages, became a frightening political reality to both the peace-loving, conservative Tamil leadership and to the oppressive Sinhala regime.

The determinant element that hardened the Tamil youth to militancy, defiance and violence was that they were the immediate targets and victims of the racist politics of successive Sinhala governments. The educated youth were confronted with appalling levels of unemployment, which offered them nothing other than a bleak future of perpetual despair. The government’s discriminatory programme of ‘standardisation’ and the racial Sinhala Only policy practically closed the doors to higher education and employment.

Plunged into the despair of unemployed existence, frustrated without the possibility of higher education, angered by the imposition of an alien language, the Tamil youth realised that the redemption to their plight lay in revolutionary politics, a politics that could pave the way for a radical and fundamental transformation of their miserable conditions of existence. The only alternative left to the Tamils under the conditions of mounting national oppression, the youth perceived, was none other than armed struggle for the total independence of their nation. Therefore, the radical Tamil youth, while making impassioned demands pressuring the old generation of the Tamil United Front leadership to advocate secession, resorted to political violence to express their militant strategy. The political violence of the Tamil youth that manifested in the early seventies should be viewed both as a militant protest against savage forms of state repression as well as the continuation of the mode of political struggle of the Tamils. The most crucial factor that propelled the Tamil United Front to move rapidly towards the path of secession and political independence was the increasing impatience, militancy and rebelliousness of the Tamil youth.

In documenting the historical origin of youth violence in Tamil politics, we should give credit to an organisation that moulded the most militant political activists and created the conditions for the emergence of the armed resistance movement of the Tamils. This organisation was the Tamil Students Federation, which produced the most determined and dedicated youth whose single-minded devotion to the cause of national freedom became an inspiration to others. The most outstanding freedom fighter that emerged from this tradition and became a martyr was a youth named Sivakumaran. The earnestness, courage and determination of this young militant in defying and challenging the authority of the Sinhala state, particularly the repressive police apparatus, became legendary. The revolutionary violence by which he kindled the flame of freedom became an inextinguishable fire that began to spread all over Tamil Eelam.

Political violence flared in the form of bombings, shootings, bank robberies and attacks on government property. A Sinhalese Minister’s car was bombed during his visit to the north. An assassination attempt was made on Mr R Thiyagarajah, a Tamil Parliamentarian who betrayed the Tamil cause by supporting the Republican Constitution. An ardent government supporter, Mr Kumarakulasingham, former chairman of the Nallur village council was shot dead. Violent incidents erupted throughout Tamil Eelam on the day the new constitution was passed. Buses were burned, government buildings were bombed and the Sinhala national flags were burned.

Confronted with widespread violence, which expressed none other than protests and rebellion against oppression, the state machinery reacted with repression and terror delegating excessive powers to the police. Empowered by law and encouraged by the state, the police practised excessive violence indiscriminately against the innocent people and primarily against the Tamil youth. The police tyranny manifested in the horrors of torture, imprisonment without trials and murders. The most abominable act of police brutality occurred on the night of the last day (10 January 1974) of the Fourth International Conference of Tamil research held in Jaffna. It was during this great cultural event, when nearly a hundred thousand Tamil people were spellbound by the eloquent speech of the great scholar from southern India, Professor Naina Mohamed, that grim tragedy struck. Hundreds of heavily armed Sinhala policemen launched a well planned, sudden attack on the spectators with tear gas bombs, batons, and rifle butts, which exploded into a gigantic commotion and stamping resulting in the tragic loss of eight lives and hundreds, including women and children, sustaining severe injuries. The event cut a deep wound in the heart of the Tamil nation; it profoundly humiliated the national pride of the Tamil people. The event betrayed the vicious character of the state police, which, in the eyes of the Tamils, became a terrorist instrument of state oppression.

The reactive violence of the Tamil youth against the terrorist violence of the racist Sinhala state assumed the character of an organised form of an armed resistance movement with the birth and growth of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

The Birth and Growth of the Liberation Tigers

The resistance campaign of the Tamil militant youth against the repressive Sinhala state, which manifested in the form of disparite outbursts of political violence in the early seventies, sought concrete political expression in an organisational structure built on a radical political theory and practice. Neither the Tamil United Front nor the Left movement offered any concrete political venue to the aspirations of the rebellious youth.

The political structure of the Tamil United Front, founded on a conservative ideology, could not provide the basis for the articulation of revolutionary politics. It became very clear to the Tamil people, and particularly to the militant youth, that the Tamil national leaders, though they fiercely championed the cause of the Tamils, had failed to formulate any concrete practical programme of political action to liberate the oppressed Tamil nation. Having exhausted all forms of popular struggle for the last three decades, having been alienated from the power structure of the Sinhala state, the Tamil politicians still clung to Parliament to air their disgruntlement, which went unheard, unheeded like vain cries in the wilderness. The strategy of the traditional Left parties was to collaborate with the Sinhala ruling class and therefore their political perspective was subsumed by the ideology of that dominant class, which was none other than Sinhala- Buddhist chauvinism. This collaborationist politics made the Left leaders turn a blind eye to the stark realities of racist state oppression against the Tamils and led them to ignore the historical conditions generated by the Tamil national struggle; it made them incapable of grasping the political aspirations of the Tamil militant youth.

The Tamil Student Federation, which was formed in 1970, articulated radical politics and encouraged student activists to take up the militant path. The Federation organised massive student protests against the government’s discriminatory educational policy of ‘standardisation’ and arranged seminars and conferences providing platforms to voice protest. Privately, the leaders of the Student Federation encouraged an armed resistance campaign as an effective and revolutionary mode of struggle against state oppression. Driven by the passion for the freedom of their motherland, dedicated young men sought guidance and leadership from the Federation. The leaders of the Federation were capable of verbal inspiration only; they were not prepared to offer leadership and guidance to carry out an effective programme of action. They lacked the knowledge and the courage to organise and spearhead an armed campaign against the repressive state apparatus. Frustrated with the impotency of the leadership of the Student Federation the disenchanted young militants resolved to launch violent campaigns, individually and as groups. As a consequence, violence flared in the form of political assassinations, bombings, shootings, arson against government property and raids on state banks. The state’s security forces, particularly the police, counter-attacked; extreme violence was used against the Tamil militants. Mass arrests, detention without trial, torture and extra-judicial killings became the order of the day. Having learned that the Tamil Student Federation was the organisation that provided encouragement and moral support to the militant youth, the police raided the offices of the Federation and arrested the leaders, including the chairman, Mr Sathiyaseelan. Subjected to intolerable torture, the leaders of the Federation confessed the names of important militant activists engaged in political violence. Faced with the threat of police hunt, the most noted militant activists went underground.

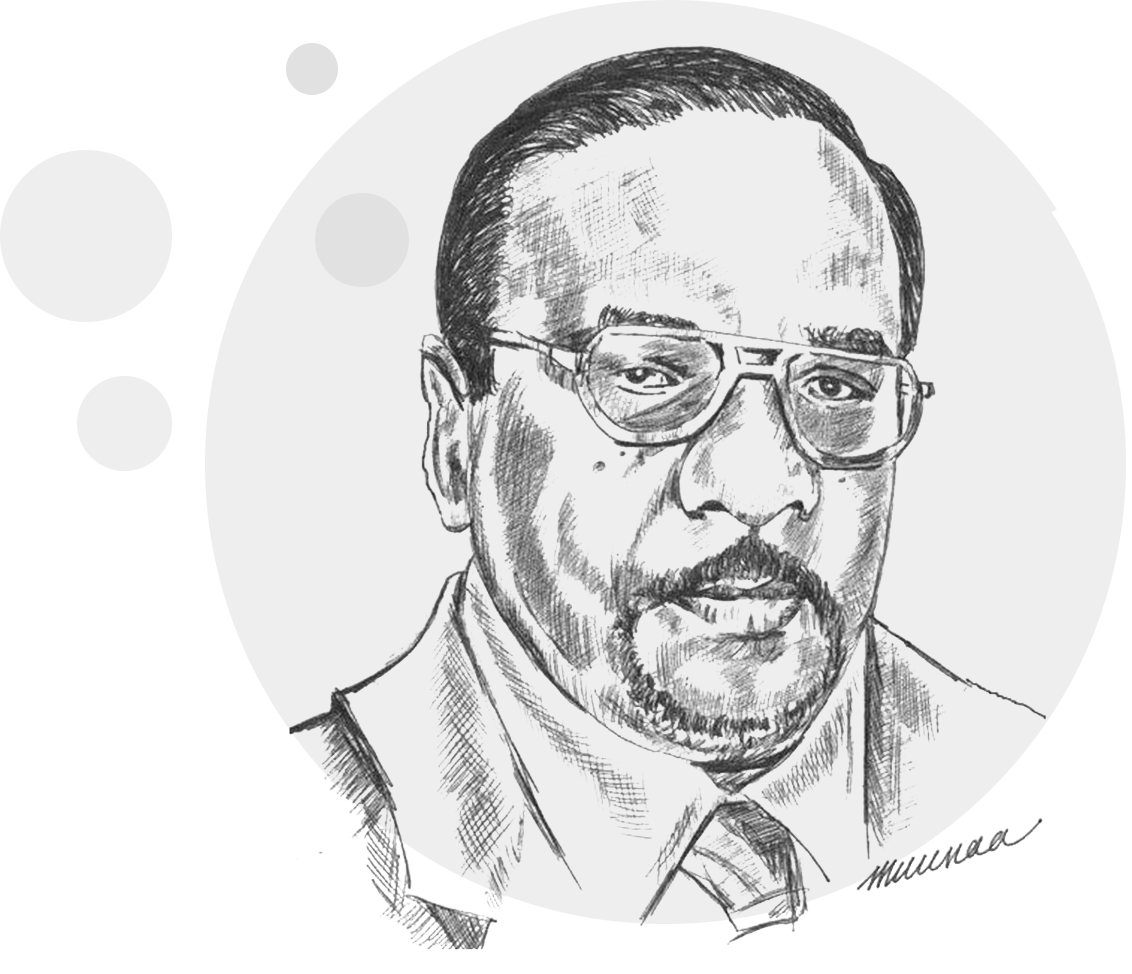

Amongst those driven underground was a dedicated young man passionately devoted to the freedom of his people. He was sixteen years old when he became a hunted fugitive, the youngest of that generation of freedom fighters. He was none other than Mr Velupillai Pirapaharan, the founder and leader of the Tamil national freedom movement – the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

Mr Pirapaharan was born on 26 November 1954 in Valvettiturai, a northern coastal town in the Jaffna peninsula. Historically Valvettiturai is renowned for its adventurous seafarers and daring smuggling exploits. But it is also famous for its militant resistance against Sinhala state repression and has produced outstandingly courageous rebels fired with the spirit of patriotism and national freedom. Mr Pirapaharan is the last child of Vallipuram Parvathy and her husband, Thiruvenkadam Velupillai. He has two sisters and a brother. His father was a government civil servant working as a District Land Officer. He is a man of exemplary character, an affable person with gentle manners, always helpful to the needy and very popular amongst his people.

In his early teens, Pirapaharan, a perceptive and sensitive person, became acutely aware of the oppressive environment in which he and his people lived. He absorbed from various sources – his family, friends, teachers and village elders – the horrendous nature of the racist oppression and the brutal atrocities perpetrated against his people. These nightmarish stories of persecution aroused intense anger and outrage in the heart of the young Pirapaharan. He felt that his oppressed people should not continue to suffer in silence but should rise up and resist the oppressor. He realised that freedom is a right to live freely in accordance with one’s choices, a state of being independent from external coercion or subjugation. He came to understand that freedom is an ideal quality of life to be fought and won requiring, in some instances, supreme sacrifices. Thus, for Pirapaharan as a young rebel, freedom became a passion and the struggle for freedom became an obsession. He lost interest in the course of study at school but was driven to learn more about human freedom and about the history of human struggles for freedom.

The turbulent history of the Indian freedom struggle fascinated Pirapaharan. While Mahatma Gandhi and his mode of political struggle based on the principle of ‘ahimsa’ attracted the Tamil politicians of that time, two famous Indian rebels who challenged British colonial rule, Subas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh were far more interesting to him. In particular he admired Subas for forming a national liberation army to launch a military campaign against British rule than the young Sikh rebel Bhagat, who confined himself to underground resistance. Pirapaharan read widely on the life and thoughts of that great Indian freedom fighter. Subas’s famous speeches became a source of inspiration to him. Pirapaharan also read Ghandi’s works. Though he admired the moral and spiritual values underlying Ghandi’s philosophy of ‘ahimsa’ he was deeply sceptical about its application as a mode of liberation struggle in the Sri Lanka context where the Sinhala state had already revealed its ugly racist face as a callous, merciless repressive apparatus. Pirapaharan was allured by the Indian epic of ‘Mahabarata’, which related the fascinating story of a great war between the forces of good and evil. Legendary Tamil emperors and their wars of conquest also enamoured him.

Inspired by the lives and works of great Indian national heroes who resisted the alien colonial rule with daring bravery, enchanted by the glorious and heroic exploits of legendary Tamil emperors, the young Pirapaharan made a resolute determination to dedicate his life to the liberation of his people. He knew the risks and perils involved in the life of a rebel fighting against an oppressive regime. Yet he was prepared to risk death for a common cause of national freedom. His underground life as a wanted fugitive at the age of sixteen turned into a nightmare when the police tightened surveillance in his village and made regular midnight raids on his house. To avoid arrest he was compelled to separate from his family and adopt a solitary life. He drifted like a gypsy, with no permanent place to rest. He hid during the daytime and moved around at night only. He often snatched a few hours of sleep on the roof of temples, in abandoned houses and hidden amongst the foliage on the ground in vegetable gardens. He was tormented by hunger. The difficulties and challenges he faced in these embryonic years of his life as a freedom fighter further strengthened his character and entrenched an iron resolve to carry on with the struggle for freedom.

As a determined young rebel living an underground life and fighting a lonely battle against formidable state machinery, Pirapaharan soon realised the futility of individual acts of political violence. His political contemporaries were, one after the other, arrested by the police and incarcerated. He also felt that some of the ‘individual operations’ were amateurish and clumsy jobs, which ended in fiasco. Having studied the incidences of militant youth violence, the negative political effects they produced and the oppressive conditions they generated, Pirapaharan realised the urgency and the historical necessity of a revolutionary political organisation to advance the task of national liberation through an organised form of armed resistance. His hope that the leaders of the Student Federation would eventually provide leadership, guidance and an organisational structure for an armed struggle soon crumbled when the leaders showed no inclination to undertake such a revolutionary task. The Federation was finally reduced to political impotency with the arrest and imprisonment of its leaders. Confronting a political vacuum and at the same time caught up in a revolutionary situation which necessitated the creation of a radical organisation to challenge the rising tide of state oppression, Pirapaharan was compelled to make a crucial decision. He finally decided to form an armed organisation under his leadership. It was in these specific historical circumstances; in 1972 the Tamil Tiger movement took its historical birth. At the time of its inauguration the movement called itself the Tamil New Tigers (TNT). Later, on 5 May 1976, the members renamed the organisation as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

Initially the Tamil Tiger movement structured itself as an urban guerrilla unit. Pirapaharan took into its ranks a group of highly dedicated and zealous young rebels who were loyal to it and prepared to die for the cause of freedom of the Tamil people. From the outset the Tamil Tigers functioned as a clandestine underground organisation practicing stringent disciplinary codes of conduct and taking an oath of allegiance to the political cause. Pirapaharan chose guerrilla warfare as a mode of armed struggle since he realised that it would be the most effective form of resistance suited to the objective ground conditions. Learning from the historical experiences of anti-colonial armed struggles in Africa and Latin America, the Tiger leader perceived that the guerrilla form of armed struggle was the classic method that could be adopted by a weak, oppressed nation to resist and fight back the organised military power of a modern state.

The disastrous failure of the JVP’s armed rebellion in southern Sri Lanka taught invaluable lessons to Pirapaharan in the art of insurrection. Theoretical models of revolutions and liberation struggles that were successful in other parts of the world could not be adopted and blindly applied in the Sri Lanka context. The specific political and historical conditions and the realities of the local ground situation had to be taken into account. The other issue of crucial importance was training in the use of weapon systems and methods of combat. Though the Tiger movement was formed in the early seventies, Pirapaharan committed a lengthy period of time to train his cadres and organise underground cells. He always resisted foreign training. He rejected an offer given to him for training in Lebanon under the Palestinian Liberation Organisation. He wanted to train his cadres on the local terrain because he knew that ultimately that was where the fighting had to take place. Pirapaharan insisted on well thought out strategy and correct tactics. There was no space for impetuousness or adventurism. From the outset of the armed campaign he has been careful to ensure the safety of his cadres and the survival of the organisation. Even though the Tamil Tigers were involved in acts of armed violence against the state police, informants and traitors, Pirapaharan kept the existence of the organisation a secret. It was not until 25 April 1978 the movement officially claimed responsibility for a series of armed operations.

The emergence of the Tamil Tiger guerrilla movement marked a new historical epoch in the nature and structure of the Tamil national struggle extending the dimension of the agitation to popular armed resistance. The LTTE soon developed a political and military structure that provided organisational expression to the aspirations of the rebellious Tamil militants who had become disenchanted with non-violent political agitations and resolved to fight back the repressive state through armed struggle. Demonstrating extraordinary talent in planning military strategy and tactics and executing them to the amazement of the enemy, Pirapaharan soon became a symbol of Tamil resistance and the LTTE he founded evolved into a revolutionary movement to spearhead the Tamil national liberation struggle.

Popular Mandate for Secession

While the Liberation Tigers were engaged in organising and developing their politico-military structure, unprecedented events of great historical significance began to unfold in the Tamil political domain. State oppression against the Tamil people deepened and became intolerable. Conciliation and co-existence between the Tamil and Sinhala nations were no longer possible. It was the time when the armed resistance movement of the LTTE emerged as a potential force demanding concrete action form the Tamil political parties. It was in these particular circumstances that, in May 1976, the Tamil United Front convened a national convention at Vaddukodai in Jaffna, where a historic resolution was adopted calling for the political independence of the Tamil nation. SJV Chelvanayakam presided over this crucial assembly where it was decided that the Tamil United Front changed its name to the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). The convention resolved to restore and reconstitute an independent state of Tamil Eelam. This famous resolution was as follows:

‘The First National Convention of the Tamil Liberation Front, meeting at Pannakam (Vaddukodai Constituency) on the 14th day of May 1976, hereby declares that the Tamils of Ceylon, by virtue of their great language, their religions, their separate culture and heritage, their history of independent existence as a separate state over a distinct territory for several centuries till they were conquered by the armed might of the European invaders and above all by their will to exist as a separate entity ruling themselves in their own territory, are a nation distinct and apart from the Sinhalese and their constitution announces to the world that their Republican Constitution of 1972 has made the Tamils a slave nation ruled by the new colonial masters, the Sinhalese, who are using the power they have wrongly usurped to deprive the Tamil nation of its territory, language, citizenship, economic life, opportunities of employment and education and thereby destroying all the attributes of nationhood of the Tamil people. And therefore, while taking note of the reservations in relation to its commitment to the setting up of a separate state of Tamil Eelam expressed by the Ceylon Workers’ Congress as a Trade Union of plantation workers, the majority of whom live and work outside the Northern and Eastern areas.

This convention resolves that the restoration and reconstitution of the Free, Sovereign, Secular, Socialist State of Tamil Eelam based on the right to self-determination inherent in every nation has become inevitable in order to safeguard the very existence of the Tamil nation in this country.’

The General Election of July 1977 was a crucial testing ground for the secessionist cause of the Tamil United Liberation Front. The TULF asked for a clear mandate from the Tamil people to wage a national struggle for political independence and accordingly the Front explicitly state in its manifesto as follows:

‘The Tamil nation must take the decision to establish its sovereignty in its homeland on the basis of its right to self-determination. The only way to announce this decision to the Sinhalese government and to the world is to vote for the Tamil United Liberation Front. The Tamil speaking representatives who get elected through these votes, while being members of the National State Assembly of Ceylon, will also form themselves into the National Assembly of Tamil Eelam which will draft a constitution for the state of Tamil Eelam and establish the independence of Tamil Eelam by bringing that constitution into operation either by peaceful means or by direct action or struggle.’

In reference to the Tamil national question, the verdict at the elections was particularly critical. The elections were fought precisely on a mandate to create an independent Tamil state. The Tamil people voted overwhelmingly in favour of the mandate electing 17 TULF candidates in the northeast. Thus, the results of the elections placed a serious, irrevocable commitment on the shoulders of the TULF leadership to take concrete steps to establish an independent Tamil state. But the Tamil Parliamentary leaders had neither political vision nor a pragmatic strategy to achieve the goal for which they were elected. They clung to their Parliamentary seats and failed to take any meaningful steps towards the path of political independence.

The general election of 1977 resulted in a massive victory for the right wing United National Party (UNP) under the leadership of JR Jayawardane which secured 85% of the seats in Parliament. The traditional Left parties were completely wiped out without a single seat and the Tamil United Liberation Front, for the first time in Sri Lanka’s political history, became the leading opposition party in Parliament. The stage was set for a confrontation: the Tamils demanding secession and separate existence as a sovereign state and the Sinhala ruling party seeking absolute state power to dominate and subjugate the will of the Tamil nation to live free. Soon after the elections, the ethnic contradiction intensified manifesting in the form of a racial holocaust unprecedented in its violence towards the Tamils.

In this island-wide racial conflagration, hundreds of Tamils were massacred and thousands of them became refugees. Millions of rupees worth of Tamil property was destroyed. The state police and the armed forces openly colluded with hooligans in their gruesome acts of arson, looting, rape and mass murder. Instead of containing the communal violence that was ravaging the whole island, government leaders made inflammatory statements with racist connotations that added fuel to the fire.

This racial violence had a profound impact on the Tamil political scene. While it reinforced the determination of the militant youth to fight for political independence, it exposed the political impotency of the Tamil Parliamentary leadership who, having failed to fulfil its pledges to the people, sought a collaborationist strategy to justify their political life. JR Jayawardane, in his Machiavellian shrewdness, soon realised that the TULF leaders were not seriously committed to the creation of an independent Tamil state but were seeking alternative political solutions. Therefore, the real threat to the Sinhala state, Jayawardane perceived, emerged from the radical politics of the militant youth. The newly elected government therefore utilized all means to crush the revolutionary youth, the very source from which the cry for freedom arose. A ruthless policy of repression was adopted by the new regime, delegating extra-powers to the police and military to clamp down on the Tamil youth. The politics of repression and resistance began to unfold into a deadly struggle intensifying the armed campaign in the Tamil homeland.

LTTE Comes to Light

The political and military significance of the LTTE’s armed resistance campaign can only be comprehended by studying various evolutionary stages of its historical growth and development. Tamil police officers and well paid civilian informants comprised a sophisticated state intelligence network, which aimed to crush the Tamil resistance campaign. The intelligence structure posed a serious threat, particularly to the newly emerging liberation movement and hence to the Tamil national cause in general. Hundreds of Tamil militants and politically active students were hunted down, tortured and imprisoned during the counter-insurgency campaign. Inevitably the LTTE, in its formative years, directed its armed campaign against the intelligence network and ultimately succeeded in severely disrupting its structure and function.

During this early stage of the guerrilla campaign the Tamil Tigers killed several intelligence police officers and informants and quislings. Yet it was a particular armed attack that alarmed the Sinhala state. Apolice raiding party, headed by a police intelligence officer notorious for the persecution and torture of militant Tamil youth, was wiped out in the northern jungle. On 7 April 1978 acting on information about the location of an LTTE military training camp, a police raiding party headed by Inspector Bastiampillai approached the site deep in the jungle near Murunkan. The police team suddenly surrounded the training camp and held the guerrillas at gunpoint. Though taken completely unawares, the LTTE fighters remained calm. One of the Tiger commando leaders, Lieutenant Chellakili Amman skilfully leapt at a police officer, snatched his sub-machine gun and shot down the police party. Inspector Bastiampillai, Sub-Inspector Perampalam, Police Constable Balasingham and police driver Sriwardane were killed on the spot. The killing of Inspector Bastiampillai was a major blow to the government. The incident created euphoria among the militant youth and signified a courageous episode of armed resistance against the repressive police.

On 25 April 1978 the Tamil Tigers, for the first time, officially claimed responsibility for the annihilation of the police raiding party and the earlier killings of police officers and Tamil informants. The press highlighted the LTTE’s claim. Thus the LTTE came to the limelight announcing itself to the world as the armed resistance movement of the Tamils committed to the goal of national liberation through armed struggle. The officially announced list claimed the assassination of Mr Alfred Duraiappah Mayor of Jaffna and the SLFP organiser for the northern region, Mr C Kanagaratnam MP for Pottuvil and some prominent police intelligence officers. The revelation of the existence of the Tamil underground resistance movement alarmed the Sinhala state. The government reacted swiftly by enacting a law in Parliament in May 1978 proscribing the LTTE. The Act was called the Proscription of Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and Other Similar Organisations. This draconian piece of legislation invested the state’s security forces with extraordinary powers to crack down on the militants. It created conditions for security forces to carry out arbitrary arrests, detention without trial for lengthy periods, torture and extra-judicial killings. The law also empowered the government to confiscate the property of any persons who supported the activities of the LTTE. Having proscribed the LTTE the government despatched to Tamil areas several contingents of armed units for the ‘Tiger Hunt’ and brought the Tamil nation under total military occupation.

Having intensified the military repression in Tamil areas, Jayawardane introduced a new constitution on 7 September 1978 which bestowed upon him absolute dictatorial executive powers and gave Sinhala language and Buddhist religion extra-ordinary status and relegated the Tamil language to second-class status. The new constitution made the President the ‘Head of State, Head of Executive and the Government and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces’ with powers to appoint and dismiss the Cabinet of Ministers and to dissolve the Parliament. The new constitution entrenched the unitary structure of the Sinhala state requiring two thirds majority in Parliament and approval of the people in a referendum for amendment or repeal of the constitution. The Tamil nation did not participate in the formulation and promulgation of the new 1978 constitution as well as the earlier 1972 constitution. While the Tamil Parliamentary party failed to organise any mass protests, the LTTE brought Tamil displeasure to the attention of the international community by blowing up and AVRO aircraft, the only passenger plane owned by the national airline on the day the new constitution was introduced to Parliament.

To stamp out the growing armed resistance, the government took repressive measures. On 20 July 1979 Jayawardane’s regime repealed the Proscription of Liberation Tigers law and replaced it with the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). This notorious law denied trial by jury, enabled the detention of people for a period of eighteen months and allowed confessions extracted under torture as admissible evidence. Having enacted the law the government declared a State of Emergency in Jaffna, and dispatched to Tamil areas more military units under the command of Brigadier Weeratunga with special instructions to wipe out ‘terrorism’ within six months. Empowered by law and encouraged by the state Brigadier Weeratunga unleashed unprecedented military terror onthe Tamils. Hundreds of innocent youths were arrested and subjected to torture. Several were shot dead and their bodies dumped on the roadside. These oppressive measures caused massive outcry and protests in the Tamil Diaspora. The International Commission of Jurists and Amnesty International in particular condemned the Terrorism Act. Brigadier Weeratungas’s six-month military campaign ended up swelling the ranks of the Liberation Tigers and turned the angry Jaffna population towards the cause of national liberation.

While the Sri Lanka state was intensifying its military domination and repression in the Tamil homeland, the LTTE leadership embarked on a plan of action to expand and consolidate the organisation. To confront the government’s counter-insurgency measures, the Tiger leaders decided to strengthen the guerrilla infrastructure and broaden the political wing. The LTTE therefore suspended all hostile armed activities against the state during the years of 1979-1980 and concentrated on the consolidation of the liberation organisation. It was during this time a programme of political action was undertaken to mobilise, politicise and organise the broad civilian population towards the national cause. A powerful international network of LTTE branches was also established in several foreign countries to carry out propaganda work.

The events that have unfolded after 1981 involved intensified military and police repression against the Tamils and increased resistance from the Tamil Tigers against the armed forces.

On midnight 31 May 1981 Sinhala police went on a wild rampage of burning in the city of Jaffna. State terrorism exploded into a mad frenzy of arson, looting and murder. Hundreds of shops were burnt to ashes; the Jaffna market square was set on fire. A Tamil newspaper office and the Jaffna MP’s house were gutted. The most abominable act of cultural genocide was the burning of the famous Jaffna public library in which more than 90,000 volumes of invaluable literary and historical works were destroyed, an act that outraged the conscience of the world Tamils. Two Cabinet Ministers, Cyril Mathew and Gamini Dissanayake of Jayawardane’s regime who were in Jaffna at the time, planned the episode and supervised the police violence.

An island wide racial conflagration flared up again just three months after the burning of Jaffna, a racial onslaught on the Tamils organised by leading members of the government, assisted by the armed forces and executed by gangs of Sinhala thugs. Hundreds of Tamils were slaughtered, thousands made homeless and millions of rupees worth of property destroyed. The repetitive pattern of this organised violence that brought colossal damage in terms of life and property to the Tamil people signified the genocidal intent underlying this horrid phenomenon. As a consequence of this heightened repression, Tiger guerrilla resistance increased with such vehemence it threw into disarray the state administrative system in Tamil areas. The LTTE’s armed campaign, at that stage, was aimed at paralysing the police administrative structure. Wellplanned attacks were directed at police patrols and at police stations effectively disrupting the law and order system that was functioning as a powerful instrument of state terror.

On 2 July 1982 Tamil Tiger guerrillas ambushed a police patrol at Nelliady, a town 16 miles from Jaffna city. In this lightening attack, four police officers were killed on the spot and three others were seriously injured. The LTTE fighters escaped without injury taking the captured weapons with them.

Lieutenant Sathiyanathan (Shankar) played a leading role in the Nelliady ambush. In a different incident he was shot in a shoot out with the police and on 27 November 1982 succumbed to his injuries in the lap of the Tiger leader Pirapaharan. He was the first martyr in the LTTE. The Tamil people mark the anniversary of his death as Heroes’ Day.